By Beth David, Editor

No doubt you’ve heard of Frederick Douglass, the runaway slave who found freedom, dignity and his first wages as a free man in New Bedford. And, no doubt, you’ve heard or have figured out that he had some help along the way.

New Bedford is home to an Underground Railroad tour, with seven stops, including the homes of abolitionists who helped escaped slaves.

Lee Blake, President of the New Bedford Historical Society, described the role of some of those people, including several women who were prominent in New Bedford’s already prominent role in the abolitionist movement. In an event on Friday, 3/17, sponsored by the Fairhaven Historical Society, Ms. Blake talked not only about the Johnsons and the Ricketstons, but also about how the women of New Bedford raised money to buy the freedom of slaves.

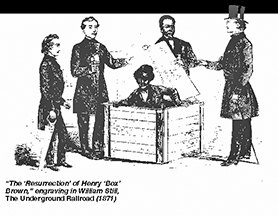

Many have heard of Henry “Box” Brown who mailed himself to freedom, but how many have heard of Isabella White, who also mailed herself to freedom?

New Bedford was poised to be a place of freedom for diverse people. The whaling industry brought people from all over the world. And the harsh working conditions required a new crop of young and hardworking men constantly. It was here that freed slaves like Mr. Douglass could make a living, earning wages equal to that of white men, based only on the work, not the color of his skin.

“You had equal access. And they really could reinvent themselves,” said Ms. Blake. “In New Bedford, we were lucky to have a strong, free African American community and a strong Quaker community really committed to ending slavery.”

Ms. Blake said that although many people were intellectually committed to ending slavery, it was not until runaway slaves started making their way north, telling their own stories, that the true human impact of slavery became clear to those who did not experience it or see it first hand. And that was the contribution of the Underground Railroad.

Henry “Box” Brown mailed himself to Philadelphia to escape slavery in 1871. Sketch from National Park Service Brochure “The Underground Railroad: New Bedford.”

“It allows people to come north and tell their truth,” said Ms. Blake. “And that’s the importance of the Underground Railroad.”

Of course, the UGRR was not really a railroad. It was a secret network of routes to the north for southern slaves.

Some traveled on foot through treacherous wilderness at night, others by boat.

Frederick Douglass worked as a caulker in New Bedford, but his first job was shoveling coal for Mrs. Peabody at 174 Union Street.

While walking toward the wharves shortly after he arrived in New Bedford, Douglass saw a pile of coal in front of the Peabody home at 174 Union Street and asked Mrs. Peabody if he might put the coal away. She consented and paid Douglass two silver half-dollars for his work:

“I was not long in accomplishing the job, when the dear lady put into my hand two silver half-dollars. To understand the emotion which swelled my heart as I clasped this money, realizing that I had no master who could take it from me — that it was mine — that my hands were my own, and could earn more of the precious coin, one must have been in some sense himself a slave.”

Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself, 1893

[From National Park Service Brochure, “Federick Douglass Freedom in New Bedford”

Douglass lived in New Bedford from 1838 until about 1843. It was there that he got “his voice as an abolitionist,” said Ms. Blake.

Although he moved to different places around the country, he never forgot that New Bedford welcomed him with open arms, said Ms. Blake. Mr. Douglass often returned, and made it a point to take his children to New Bedford and show them where he lived there.

“Douglass is really an amazing individual,” said Ms. Blake, explaining how he realized how important good “speechifying” was and taught himself to orate.

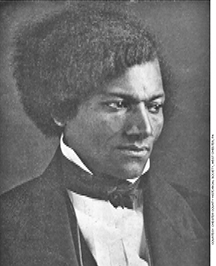

Frederick Douglass believed in the power of photographs to create a new image of black people in America. Photo from National Park Service Brochure

She said he was the most photographed man in America and wrote about the importance of capturing one’s image and how it could change the way people talk about a person, or a race. And, indeed, his photographs show a dignifed man with a serious nature.

The NB Historical Society has secured property and the funds to create “Abolition Row Park” at an empty lot on Spring and Seventh Streets in New Bedford. Ms. Blake said about 19 historic homes are in that immediate vicinity. The park will have educational kiosks and point out historic sites in the neighborhood.

“New Bedford is really an authentic place,” said Ms. Blake after the talk.

“She really does bring history alive,” said D’arcy MacMahon, especially the “role New Bedford played in the abolitionist movement. We know so much about Whaling [in New Bedford], but not much about all the connections.”

Visit www.nbhistoricalsociety.org.

Click here to download the entire 3/23/17 issue: 03-23-17 issDouglassTalk